Are the gates of Indian heaven closed for Big Tech now?

According to the recent data published by the Indian government, more than half a billion Indians joined the Internet since the early 2010s. Of course, there are many other events taking place there in the recent months. However, now the country has twice as many users as there are in the United States.

Of course, it was quite predictable that Big Tech will rush in to get its piece of cake. Namely, Facebook (FB) CEO Mark Zuckerberg and Twitter (TWTR) CEO Jack Dorsey both visited India to meet with the country’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi. And so did Google (GOOGL) CEO Sundar Pichai and Microsoft (MSFT) CEO Satya Nadella, who both were actually born in India. Amazon’s CEO Jeff Bezos also visited India earlier this year.

All of those tech giants, including Netflix and Uber, invested billions of dollars into their Indian partners and presented several “India-first” features and local language versions of their platforms. Asian peers like SoftBank (SFTBF), Tencent (TCEHY), Bytedance and Alibaba (BABA) were not wasting their time either and also made huge investments into the economy of the country, mostly into the India-based young startups.

However, those days are now over as India has started to make changes to the rules of operating in the country. That, in turn, can possibly mean that there could be certain complications for global tech firms that wish to start their operations in India and profit from its massive market.

The regulations promised to be implemented in the foreseeable future are most likely to include the collection and storage of data, selling of products online and protecting users’ privacy.

It goes without saying that with nearly 700 million internet users and almost an equal number of people yet to come online for the first time, India can be a very attractive market for companies worldwide. However, all recent restrictions on foreign tech companies and government intervention in controlling the internet are creating concerns that the world’s largest democracy is moving closer to China’s policy on the freedom of speech online.

Mishi Choudhary, co-founder and legal director of New York-based tech advocacy group Software Freedom Law Center, commented:

“A heavy-handed government that wishes to use technology to surveil its own citizens or control the narrative by curtailing their free speech and expression is not interested in using technology for the good but merely to control…In such scenarios comparisons with the Chinese authoritarian internet are natural.”

What India will decide to do will affect not only the country itself but also many other countries outside of the region.

Jeff Paine, managing director of the Asia Internet Coalition, a tech industry group whose members include Google, Facebook, Amazon, and Twitter, said:

“India’s potential and opportunity are undisputed, however its attempt to artificially ringfence itself from the global digital economy is concerning…We hope policy makers will take a holistic and long-term view.”

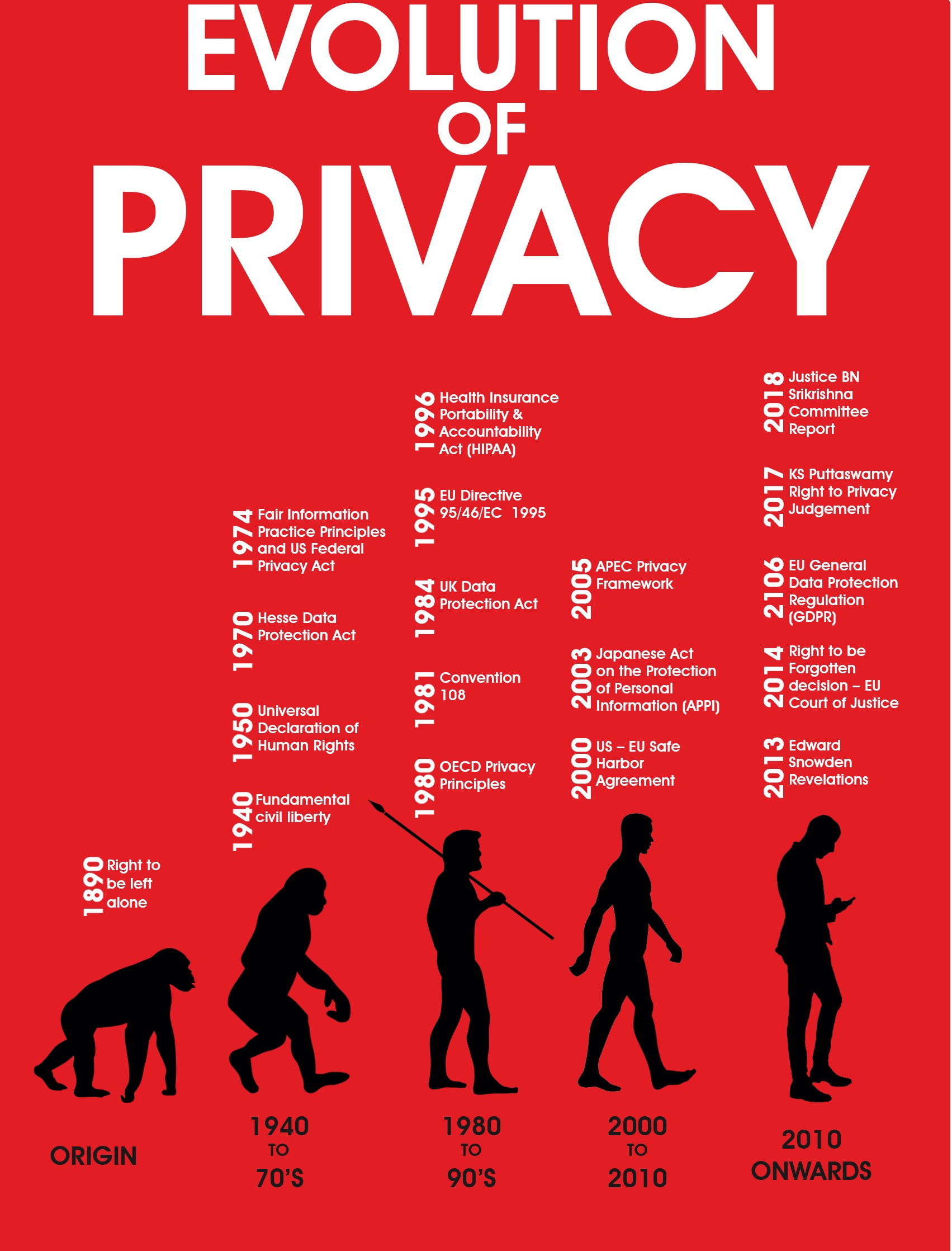

Data usage and privacy policies

It is believed that the main focus will be on how tech companies are storing and using the personal data of users.

Under the new Data Protection Bill of India, tech companies are required to inform users about the information they store and, therefore, get a direct agreement from the users to do that. That rule imposes restrictions on what kind of Indian data will be allowed to be stored outside of the country.

Even though the bill was not yet fully adopted and is just making its way to India’s parliament, many compare it to the European Union’s data protection law, also known as GDPR, which was passed back in 2018. Therefore, there are some experts who are concerned that the new India’s law can go through the same pathway the EU took, meaning that even though this law stands for control of users over their personal data, it gives the Indian government a great power as well. And one of the reasons for the concerns is that the Indian government can exempt its own agencies from following the rule, which means that these agencies can easily collect and use personal data for their own benefit.

Choudhary mentioned:

“The current data protection legislation lacks people protection and gives government a supra interest over everyone.”

She also added:

“They will be forced to make the choice between privately kowtowing to all demands or resisting extra-judicial demands on their users…An informed, empowered user will not settle for any piece of technology that sells them to authorities without any legal basis.”

In theory, the government will also be capable of deciding which personal data will be stored within the country and which can go outside of its borders.

Jay Gullish, the head of tech policy at the US-India Business Council, has also brought some light to his opinion regarding the new law:

“These are global companies, they’re global operations, they’re global products and services, and in many instances there’s an actual need to have data move back and forth pretty regularly … I think the concern now is that the bill … is clearly not along the lighter side of regulation.”

All that uncertainty about what might happen next keeps many large companies from investing in India. Gullish explained:

“Companies don’t want to have multiple operations, different processes in different countries.”

Earlier, in one of the interviews, Nadella stated that Microsoft would “fully conform to the laws” India puts in place. He also said that the company has already invested in better localization of data at its Indian data centers.

Moreover, Google spokespeople reassured that the new regulations in India will not in any way hurt the tech growth in that region.

Google’s then-India head Rajan Anandan said:

“I think data localization of any form slows down the internet economy and innovation in countries. We’re hoping that India will be progressive.”

Possible outcomes

The data bill isn’t the only one creating concerns on the Indian market. Thus, new e-commerce rules implemented last year restricted several Amazon and Flipkart operations, one of which was the steep discounts that allowed the companies to dominate the Indian market which is believed to be worth $200 billion by 2027.

What is more, it was announced that the government is seriously thinking about imposing a 1% tax on every transaction on e-commerce platforms based in India.

Many are concerned that constraining big global firms could backfire on India’s broader e-commerce industry. Paine even commented on this issue:

“Overly prescriptive regulation and onerous compliance obligations … would act as market barriers and stifle growth and competitiveness…it could also significantly restrict consumer choice and access, creating a lag for Indian consumers behind global contemporaries.”

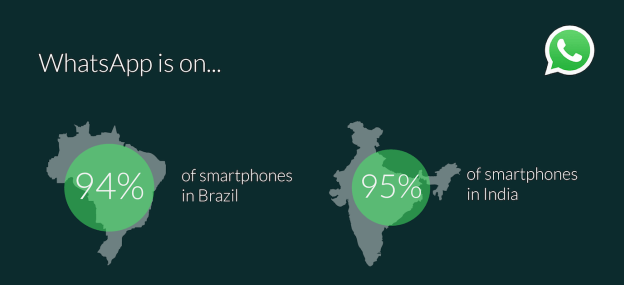

Moving further, we can see the recent requirement of the Indian government for companies like WhatsApp to trace individual messages that the government deems a threat. However, WhatsApp has repeatedly refused to do so, stating that encryption and privacy are two fundamental points the company is based on.

Hannah Quay-de la Vallee, a senior technologist at the Center for Democracy and Technology, wrote in one of her recent blogs:

“If this rule is implemented in India (and potentially copied by other nations) it could force companies to create two types of systems — one that uses and one that doesn’t. Companies might well justifiably balk at the cost and complexity of that approach and simply build less secure systems.”

She then also added:

“Alternatively they could remove themselves from the Indian market altogether, depriving 1.2 billion people of state-of-the-art internet security…Neither of these are good outcomes.”

The China model

India became an attractive market for many large tech companies because of its openness. Therefore, after companies like Google, Facebook, and Twitter shut their operations in China, where the market became too reserved and strict, it was quite obvious for everybody that they will most likely transfer to India. And this is exactly what has happened.

However, the main issue today is that even though India’s Internet is still quite open, the new governmental regulations that are expected to be implemented soon raised red flags.

Dipayan Ghosh, co-director of the Platform Accountability Project at Harvard University’s Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy, commented:

“The divide between east and west on matters of internet governance — and more broadly, freedom of expression and open access to information — is stark.”

While there are experts like Dipayan Ghosh, there are also others who are convinced that there is a high possibility of India moving closer to China in the way the country is managing media and tech industries.

Ghosh said:

“The world is trying to move in the direction of democracy and openness, and a few countries are moving the other way — closing down pathways for exchange and suppressing threats to incumbent governmental power … Should India choose the latter path, it will doubtless rankle many around the world and spell trouble for India’s standing, politically and economically.”

However, all in all, regardless of the hardships and inconvenience the Indian government might create for the foreign tech companies, they are unlikely to leave the market because they simply cannot afford to do that.

Comments (0 comment(s))